Manageable Stressor: Compassion Fatigue

The exhaustion from prolonged emotional caregiving.

Healthcare professionals dedicate themselves to caring for others, often forming deep emotional connections with their patients. However, when the demand for compassion outweighs a person’s ability to recover, it can lead to compassion fatigue (CF)—a state of deep emotional and physical exhaustion that makes it difficult to engage with patients and find meaning in work [1-8].

What is Compassion Fatigue?

Compassion fatigue occurs when the continuous emotional strain of caregiving depletes a person’s energy and well-being. It is characterized by:

- Emotional exhaustion—feeling drained, numb, or detached [2-4].

- Reduced empathy—a diminished ability to connect with patients and colleagues [3, 4].

- Poor work performance—losing a sense of purpose in one’s work [1, 2].

Unlike burnout, which stems from workplace conditions, compassion fatigue is caused by the emotional demands of caregiving. Without support, it can lead to withdrawal, disengagement, and an increased risk of errors in care [3-6].

Recognizing Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue can be subtle at first, but early warning signs tend to appear in high-intensity environments such as critical care, oncology, mental health, and long-term caregiving roles [2-4, 6]. Employers should watch for:

- Workplace Signs: Avoiding patient interactions, decreased job satisfaction, increased mistakes [2, 4-6].

- Behavioral Changes: Emotional withdrawal, detachment from work, reduced social interaction [2-4, 6].

- Emotional Shifts: Irritability, sadness, numbness, loss of fulfillment [2, 3, 5, 6].

- Physical Symptoms: Chronic fatigue, headaches, insomnia, muscle tension [3, 4, 6].

Recognizing these signs early allows for intervention before CF impacts both staff well-being and patient care quality.

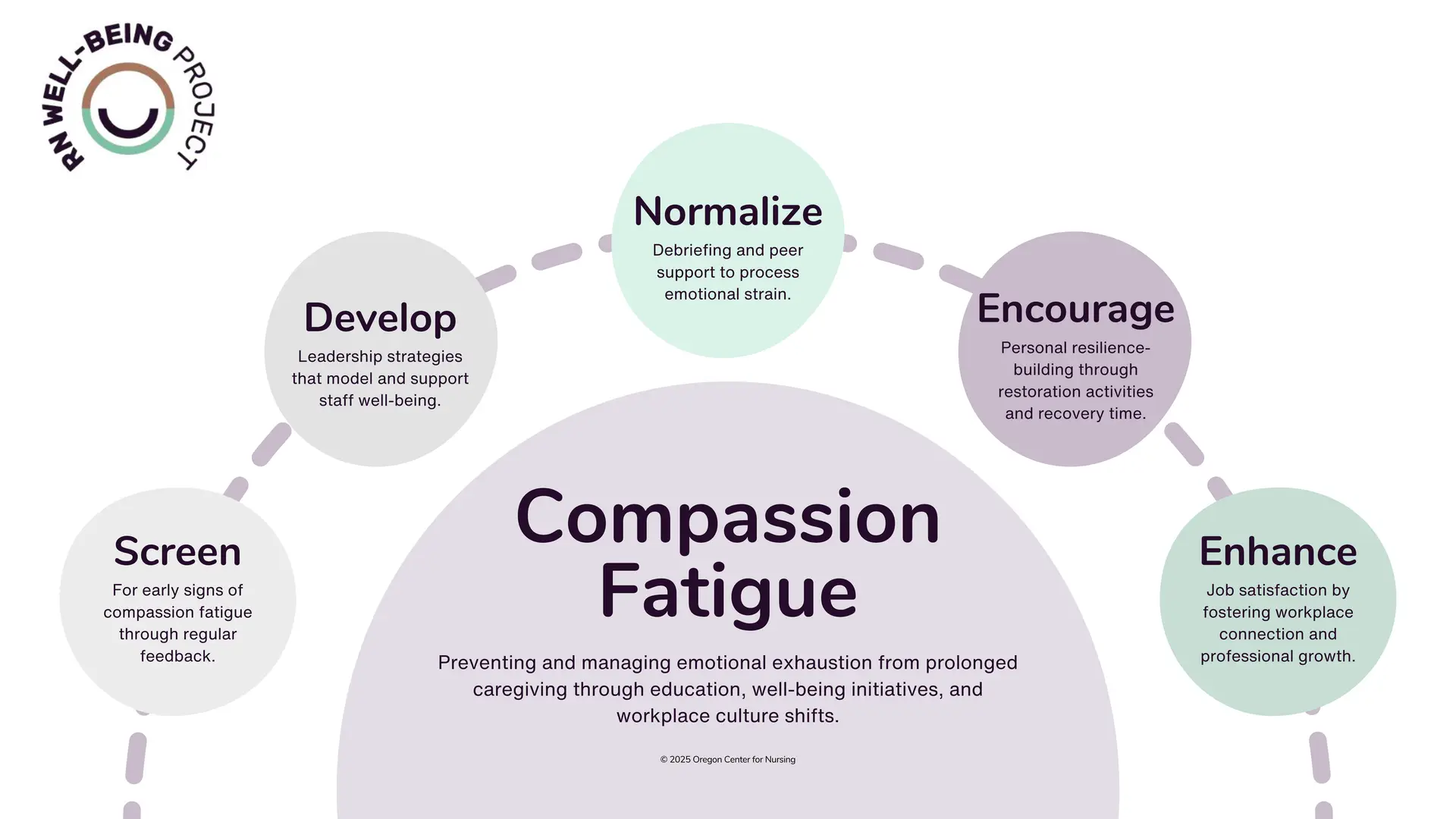

Preventing & Addressing Compassion Fatigue

Organizations can reduce the risk of compassion fatigue by focusing on workplace resilience, leadership engagement, and structured emotional support.

By embedding compassion fatigue awareness into workplace policies and daily practice, organizations can help professionals maintain emotional resilience, job satisfaction, and high-quality patient care.

Addressing Compassion Fatigue

- Regular Screening: Monitor for early signs of CF through structured self-assessments and feedback [2-4].

- Education & Coping Strategies: Provide training on self-monitoring, emotional resilience, and personal recovery techniques [3-5].

- Clinical Supervision & Debriefing: Facilitate reflective supervision and group debriefing to help staff process emotional strain [2-4].

- Work-Life Balance Support: Encourage staff to prioritize well-being through structured breaks and sustainable schedules [2, 3, 6].

- Leadership Modeling: Train managers to recognize CF, provide validation, and foster a workplace culture that prioritizes emotional well-being [4-6].

Supporting Affected Staff

- Access to Mental Health Resources: Ensure the availability of counseling, peer support, and resilience-building programs [2, 3, 6].

- Team-Based Coping Strategies: Promote social support, emotional processing, and shared resilience-building efforts within teams [4-6].

- Structured Feedback & Professional Development: Encourage career growth and job satisfaction through structured mentorship and skill-building opportunities [2, 4, 6].

- Mindfulness & Stress Reduction Practices: Integrate workplace mindfulness training and relaxation techniques to help staff recover [3, 4, 6].

- Managerial Support & Workplace Engagement: Create an environment where staff feel valued, heard, and supported in managing emotional strain [2, 4, 5].

References

[1] Isobel, S., & Thomas, M. (2021). Vicarious trauma and nursing: An integrative review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12953

[2] Paiva-Salisbury, M. L., & Schwanz, K. A. (2022). Building Compassion Fatigue Resilience: Awareness, Prevention, and Intervention for Pre-Professionals and Current Practitioners. Journal of Health Service Psychology, 48(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42843-022-00054-9

[3] Alharbi, J., Jackson, D., & Usher, K. (2019). Compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. Saudi Medical Journal, 40(11), 1087–1097. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2019.11.24569

[4] Marshman, C., & Hansen, A. (2021). Compassion fatigue in mental health nurses: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12812

[5] Cavanagh, N., Cockett, G., Heinrich, C., Doig, L., Fiest, K. M., Guichon, J. R., Page, S., Mitchell, I., & Doig, C. (2019). Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nursing Ethics, 27(3), 639–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019889400

[6] Xie, W., Wang, J., Okoli, C. T., He, H., Feng, F., Zhuang, L., Tang, P., Zeng, L., & Jin, M. (2020). Prevalence and factors of compassion fatigue among Chinese psychiatric nurses. Medicine, 99(29), e21083. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000021083

[7] Roberts, C., Darroch, F., Giles, A. R., & Van Bruggen, R. (2022). You’re carrying so many people’s stories: vicarious trauma among fly-in fly-out mental health service providers in Canada. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2022.2040089

[8] Stoewen, D. L. (2019a). Moving from compassion fatigue to compassion resilience Part 1: Compassion – A health care priority, core value, and ethical imperative. PubMed, 60(7), 783–784. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31281199

[9] Stoewen, D. L. (2019b). Moving from compassion fatigue to compassion resilience Part 2: Understanding compassion fatigue. PubMed, 60(9), 1004–1006. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31523091