Manageable Stressor: Secondary Traumatic Stress

The stress reaction to indirect exposure to trauma.

Healthcare professionals don’t just witness trauma—they also hear about it, read about it, and carry the weight of their patients’ stories. This exposure can take a serious toll. Secondary traumatic stress (STS) is a natural reaction to this indirect trauma, triggering symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder [1-6].

What is Secondary Traumatic Stress?

Healthcare professionals don’t just witness trauma—they also hear about it, read about it, and carry the weight of their patients’ stories. This exposure can take a serious toll. Secondary traumatic stress (STS) is a natural reaction to this indirect trauma, triggering symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder [1-6].

STS happens when indirect exposure to patients’ trauma triggers a strong stress reaction. It can show up in:

- Emotional reactions like sadness, guilt, or anger.

- Cognitive effects such as intrusive thoughts, difficulty concentrating, or avoiding reminders of trauma.

- Physical symptoms like exhaustion, sleep disturbances, or feeling constantly on edge.

Unlike vicarious trauma, which builds gradually, STS can hit suddenly after a distressing event. Workload, lack of support, and personal stress can all increase risk. Recognizing STS early is key to preventing long-term consequences [5, 7, 8].

Recognizing Secondary Traumatic Stress

STS isn’t always obvious, but it tends to surface more commonly in high-exposure settings like emergency rooms, mental health services, and palliative care. Employers should watch for:

- Workplace Signs: Increased absenteeism, reduced focus, decreased productivity [1, 4, 4].

- Behavioral Changes: Withdrawal, avoidance, increased irritability or agitation, trouble concentrating [1, 2, 4-7, 10].

- Emotional Shifts: Anxiety, numbness, guilt, distress [1, 6, 9].

- Physical Symptoms: Sleep issues, fatigue/exhaustion, heightened startle response [1, 6, 7, 10].

Identifying STS early can help prevent long-term psychological distress and workplace disruptions.

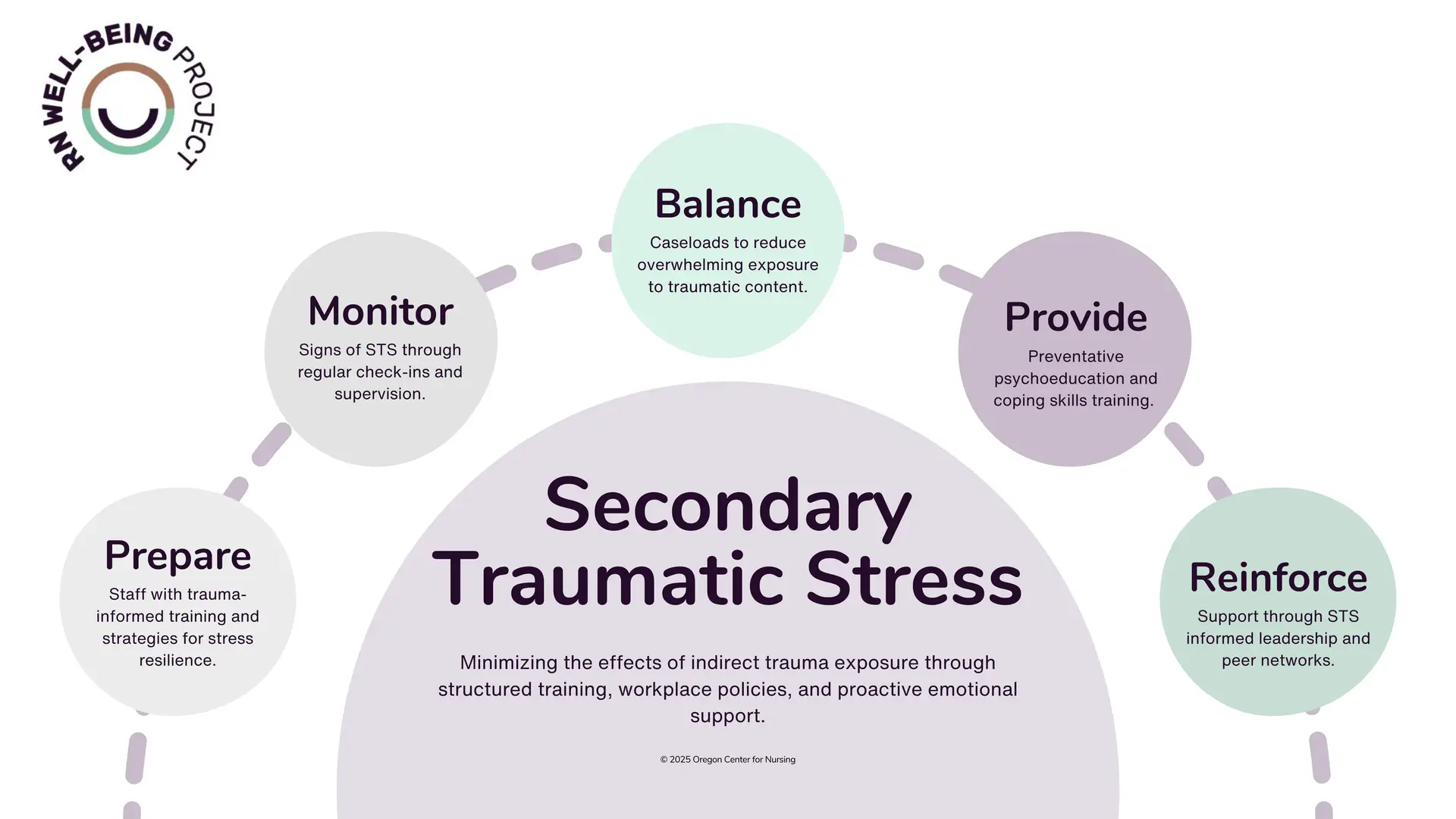

Preventing & Addressing Secondary Traumatic Stress

Even with unavoidable trauma exposure, organizations can take proactive steps to reduce its impact. Prevention begins with awareness, structured recovery opportunities, and a trauma-informed workplace culture. When STS does occur, early intervention and support systems are essential to help staff recover and re-engage in their work.

Preventing Secondary Traumatic Stress

- Develop Guidelines & Policies: Create STS-specific policies, realistic job previews, and training to improve occupational fit [3, 5].

- Enhance Occupational Fit: Adjust workloads to balance trauma exposure and reduce unnecessary stressors like role conflicts [11].

- Trauma-Informed Care Training: Train staff in trauma-informed care to build resiliency, improve supervision, and promote psychological safety [5].

- Empathy-Based Stress Awareness: Integrate STS-related stress awareness programs to help professionals detach from work stress [3, 12].

- Preventive Psychoeducation: Conduct universal STS education on indirect trauma exposure, self-care, and personal resilience skills [5].

Supporting Affected Staff

- Supportive Supervision: Implement supervisory models that include frequent check-ins, open discussions, and balancing STS exposure [4, 7, 12].

- Organizational Support & Training: Provide STS-specific supervisory support, targeted caseload assignments, and Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) [1, 4, 12].

- Career Development & Feedback: Offer structured career development programs, constructive feedback, and professional growth opportunities [3,11].

- Mindfulness & Coping Interventions: Include mindfulness training, journaling, mentoring, and coping strategy education in well-being programs. [3]

- Clinical Supervision & Debriefing: Strengthen supervision models to facilitate ongoing monitoring of STS and normalize debriefing after traumatic cases [1, 4, 7, 12].

References

[1] Blanco‐Donoso, L. M., Moreno-Jiménez, J., Amutio, A., Gallego-Alberto, L., Moreno‐Jiménez, B., & Garrosa, E. (2020). Stressors, job resources, fear of contagion, and secondary traumatic stress among nursing home workers in face of the COVID-19: the case of Spain. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(3), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820964153

[2] Ogińska-Bulik, N., Gurowiec, P. J., Michalska, P., & Kȩdra, E. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of secondary traumatic stress symptoms in health care professionals working with trauma victims: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0247596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247596

[3] Rauvola, R. S., Vega, D. M., & Lavigne, K. N. (2019). Compassion Fatigue, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Vicarious Traumatization: a Qualitative Review and Research Agenda. Occupational Health Science, 3(3), 297–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-019-00045-1

[4] Quinn, A., Ji, P., & Nackerud, L. (2018). Predictors of secondary traumatic stress among social workers: Supervision, income, and caseload size. Journal of Social Work, 19(4), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318762450

[5] Sprang, G., Ford, J. D., Kerig, P. K., & Bride, B. E. (2019). Defining secondary traumatic stress and developing targeted assessments and interventions: Lessons learned from research and leading experts. Traumatology, 25(2), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000180

[6] Marković, M. V., & Živanović, M. (2022). Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12881. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912881

[7] Mistry, D., Gozna, L., & Cassidy, T. (2021). Psychological and the physical health impacts of forensic workplace trauma. Journal of Forensic Practice, 24(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/jfp-05-2021-0027

[8] Cummings, C., Singer, J., Hisaka, R., & Benuto, L. T. (2018). Compassion satisfaction to combat work-related burnout, vicarious trauma, and secondary traumatic stress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), NP5304–NP5319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518799502

[9] Marsac, M. L., & Ragsdale, L. B. (2020). Tips for recognizing, managing secondary traumatic stress in yourself. AAP News. https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/05/21/wellness052120

[10] Xu, W., Masters, G. A., Simas, T. A. M., Bergman, A. L., & Byatt, N. (2023). Labor and Delivery Clinician perspectives on impact of traumatic clinical experiences and need for systemic supports. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 27(9), 1651–1662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03708-2

[11] Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz‐Vergel, A. I. (2023). Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933

[12] Sprang, G., Whitt‐Woosley, A., Wozniak, J., Gusler, S., Hood, C. O., Kinnish, K., & Stroup, H. E. (2023). A Socioecological Approach to Understanding Secondary Trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(21–22), 11745–11767. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605231188047